ChesterBelloc: Of Fat Men, Forgotten Kings, and the Virtues Disney Lost

By Caleb Brown and Connor Mortel

The Servile State Re-Animated: Wall•E and the Rediscovery of Life

By Caleb Brown

Nick Land:

“Capitalism is not a human construct but a planetary technovirus, consuming intelligence and wiring it into ever more productive circuits.”

Ted Kaczynski:

“The industrial-technological system may survive or it may break down. If it survives, it will probably do so by making human beings obsolete.”

Byung-Chul Han:

“What we call freedom today is nothing but the freedom to perform.”

Hilaire Belloc:

“The control of the means of production by a few is the mark of the servile state. The rest must serve.”

With quotes like that opening the essay, you’re probably expecting a breakdown of the Servile Age or an attempt to decode Nick Land’s singularity. Instead, we’re going to talk about a robot in love, fat humans, and a plant in a boot.

Wall•E is a deeply theological film. While many read it as a cautionary tale warning against pollution and calling for an environmentally friendly approach to reality, and while those themes are present, they are only surface readings of the story. This will not be a play-by-play of the movie, rather, I will be highlighting certain scenes and themes about the movie. First, let me set the stage.

We open some time in the (we hope) distant future. The Earth is covered in nothing but trash and a lone robot is cleaning it. Wall•E, like the biblical Adam, is alone tending to the Earth. We see that every night, Wall•E watches Hello Dolly, a 1969 musical. Upon seeing two characters in the musical hold hands, Wall•E clasps his hands together to simulate the act he’s seeing on film, demonstrating to us his desire for communion. His loneliness is interrupted when Eve shows up. (I shouldn’t have to point out the biblical parallels.) Soon, Eve finds what she was sent for. On the desolate, trash-covered mess that is Earth, she finds one little plant, a stem with a few leaves resting in a makeshift pot, a work boot. And I won’t spoil the rest of the film—you should definitely check it out. I will, however, touch on three scenes.

(Minor spoilers ahead.)

The first humans we see in the movie are living a “perfect” life: they have all of their perceived needs satisfied, floating along in reclined chairs with screens before their eyes and all their sustenance coming from shakes.

One of the first things we see Wall•E do once aboard this sci-fi cruise ship is knock a man out of his chair. As the man is on the ground, the glowing blue paths that they all float around on divert around him. His fellow men and women fly past him without even giving him notice. He reaches out asking for help. This is our first clear example of how despite having all their material needs for food and entertainment satisfied, something human is missing. The only reason the man is able to get back into his chair is that our protagonist Wall•E, helps him up.

The Venerable Fulton J. Sheen once said,

“The danger of the future is that men may become robots, and the robots may become men.”

That’s precisely what we are seeing in the movie. As man has every one of his physical needs satisfied through technology, he becomes just another part of the ship.

“What we call freedom today is simply the freedom to choose between products, to consume. It is not real freedom, but a form of control.”

This quote from Byung-Chul Han sums up the state of the human race as we find them in Wall•E. Their chairs run on tracks; they lack even the freedom to choose their own road, only free to choose what shake they drink and what games they play.

But as Wall•E and Eve run throughout the ship, we see our three main human characters begin to exert their freedom. The man Wall•E knocked down and a woman Wall•E met are seen playing together in a pool, splashing each other with water. As the pool closes and the robots come by informing the blossoming couple that the pool is closed, they splash the robot, causing it to short circuit. Here we see our first example of humans rejecting the rule of the machines, not in the name of selfish desires to consume but in the desire to keep the romantic encounter going. We even see that the chairs they live on aren’t on the tracks anymore; rather, they are freely floating above the water, symbolizing their newfound freedom.

While our two human characters rediscover their humanity, we see that our third human character is going along a similar path not through human connection but through a longing for home he didn’t know he had.

The Captain vs Auto, Life vs Survival

The Captain, like every other human on the Axiom, is obese, slow, and dependent on the robots. One robot in particular—Auto (short for autopilot)—serves as the ship's computer, clearly inspired by HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey (this is not the only reference to Kubrick’s fantastic film, but we will get to that later). Scanning some dirt Wall•E brought in, the Captain asks the computer to define Earth, causing the computer to bring up several photos and videos of our planet: rivers, farms, people dancing. The Captain, with a clear look of amazement in his eyes, proceeds to study Earth.

Hilaire Belloc once said,

“It is the loss of the sense of home, the exile from one's natural state, that breeds the profoundest despair."

What we see in the Captain’s eyes, body language, and voice is that he is instantly reminded of his home—a home he’s never been to—but immediately longs for; he has been shaken awake by the beauty of his long-lost and forgotten Home.

When Eve finally presents the plant in the boot (if the plant represents new life, does the boot represent man’s rediscovery of labor?), the Captain is seen to care, and water the plant as soon as he grasps it. He proceeds to ask Auto to fire up the “holo-detector” so the ship can plot its course home. And this is where the most realistic Artificial Intelligence antagonist in film is revealed: Auto tells the Captain to give him the plant and informs him that “we cannot go home.” When the Captain demands an answer, Auto simply responds “classified” and tries to grab the plant from the Captain.

The Captain, shocked to hear of classified information, says,

“You don’t keep secrets from the captain. Tell me, Auto.”

Auto, obeying orders, reveals to the Captain that 700 years ago, the Global CEO of Buy-N-Large—the company that built the ship and everything humans use—sent a secret message to autopilot informing him that operation cleanup was a failure, that rising levels of toxicity had made life on Earth unsustainable, and instructed Auto to keep the ship in space, canceling Operation Recolonize.

Now this next scene is so important to the points I wish to make that I will simply post the transcript:

CAPTAIN:

That's — that's nearly 700 years ago!! Auto, things have changed! We've got to go back!

AUTOPILOT:

Sir, orders are: "Do not return to Earth."

CAPTAIN:

But life is sustainable now! Look at this plant, green and growing! It's living proof he was wrong.

AUTOPILOT:

Irrelevant, Captain.

CAPTAIN:

What?! It's completely relevant! (points out to space) Out there is our home! Home, Auto! And it's in trouble! I can't just sit here and... and... do nothing! That's all I've done! That's all anyone on this blasted ship has ever done... NOTHING!!

AUTOPILOT:

On the Axiom you will survive.

CAPTAIN:

I DON'T WANT TO SURVIVE! I WANT TO LIVE!

AUTOPILOT:

Must follow my directive.

The Captain turns away in frustration. His eyes catch sight of the CAPTAIN PORTRAITS. He notices AUTO in every one of them, looking over all their shoulders—a little closer every generation. The Captain slowly looks over his shoulder... and Auto is right behind him.

The Captain looks at the plant in his lap. His countenance grows determined. He rights his hat... turns to face Auto... and gives the most authoritative order of his career:

CAPTAIN:

I'm the Captain of the Axiom. We are going home today!

There is so much that could be said about this scene: from the cold logic and insistence on following protocol by Auto (a villain without malice, only following his programming) to the Captain’s impassioned cry of “I DON’T WANT TO JUST SURVIVE I WANT TO LIVE,” to the brilliant animation move of having the previous Captains appear in live action, slowly morphing into the overweight blobs we see in the film—and Auto’s slow advance in each portrait demonstrating the machine’s slow creep from helpers to rulers.

Belloc said,

“A man who has lost his home has ceased to be fully human.”

Bishop Fulton Sheen said,

"Life is worth living only when it is lived for something worth dying for."

What we see in this scene is a man discovering his home, his purpose, and his will.

"The glory of God is man fully alive,"

and here we see a man wake up from his life of constant comfort and positivity. The Captain does not know what Earth is like now; he has not seen the towers of trash, the dust storms, or the atmosphere so littered with satellites and debris that it nearly blocks out the sun. He has no clue about the work needed to rebuild his home. He just knows,

“Out there is home—and it’s in trouble.”

But Auto will not break his programming. He captures the plant and sends the Captain to his room. The AI nanny state has sent the supposed leader of the people to his room, fully cementing the rule of the Machine that Ted Kaczynski talked about (see quote from the beginning).

But the Captain does not give up. He begins pulling out cables and tricks Auto into believing that he has the plant, taunting Auto,

"You want it? Come and get it, Blinky."

One thing we notice in this scene is the Captain’s infectious joy—he’s laughing and smiling as he fights for his home. He has a purpose, he has a goal, he is fully alive, reveling in his newfound motivation.

Before we can wrap up the Captain’s story, let’s return to the movie’s namesake, Wall•E.

Wall•E, Eve, Love, and Sacrifice

In the climax of the film, we see our robotic heroes fighting through the service bots sent after them by Auto. As the holo-detector rises from the ground, our heroes desperately rush to it. Auto, seeing this, tilts the ship, causing the humans and robots to slide to the left. During this confusion, Auto begins to lower the holo-detector.

Wall•E, seeing this, charges forward and places his body between the holo-detector and the floor, holding it in place.

Now what’s interesting to note is that Wall•E has no clue what is going on. He does not know why the plant needs to go into the holo-detector or that it means humans and Eve will return to Earth. All he knows is that Eve wants the plant in the holo-detector, and he is willing to place himself in harm's way to see her wishes fulfilled.

During this climactic scene, we see the Captain battling Auto for dominance. Auto flings the Captain away, knocking him down. Given the Captain’s weight and size, he is unable to pick himself back up—the machines have won. Man is knocked down and unable to rise again. Auto, returning to the control board, surges the lowering of the holo-detector, crushing Wall•E.

The Captain, seeing this robot’s sacrifice, finds his strength. To the music of Also Sprach Zarathustra (see, I told you we weren’t done with 2001: A Space Odyssey), he lunges at Auto and reaches for a switch at the top of Auto’s cane. He switches Auto from "auto" to "manual." (A switch from automatic labor to manual labor?)

Rectifying the ship's proper alignment, Eve places the plant inside the holo-detector, and humanity heads home. We see the men and women of the Axiom planting the boot into the ground, symbolizing the beginning of their effort to clean up and save their home.

In the movie’s credits, we see both man and machine cleaning and rebuilding together. Our final shot is a picture of a large, fully formed tree with its roots growing down into the old boot.

“But is Wall•E okay?”

If you must know, go watch the movie for yourself.

In conclusion, Wall•E is not some bland children's movie about cute robots and recycling. It is a profound tale about what happens when survival replaces life, when comfort replaces freedom, and when the machine replaces the soul.

Nick Land warned that capitalism itself had become a planetary technovirus—an intelligence wiring human desire into ever more efficient circuits. Ted Kaczynski warned that the technological system would make human beings obsolete, kept alive only for survival, not for living. Byung-Chul Han reminded us that true freedom is not the ability to perform but the ability to live authentically. And Hilaire Belloc saw clearly that the loss of economic and cultural sovereignty—the loss of home—would turn men into slaves.

Wall•E shows us all of this, not through dry treatises, but through the story of a robot who loves without calculation, of a Captain who stands up and takes back his destiny, and of a humanity that, after centuries of drifting, remembers what it means to live—and to labor—again.

It is not enough to survive.

It never was.

Leo Rex

By Connor Mortel

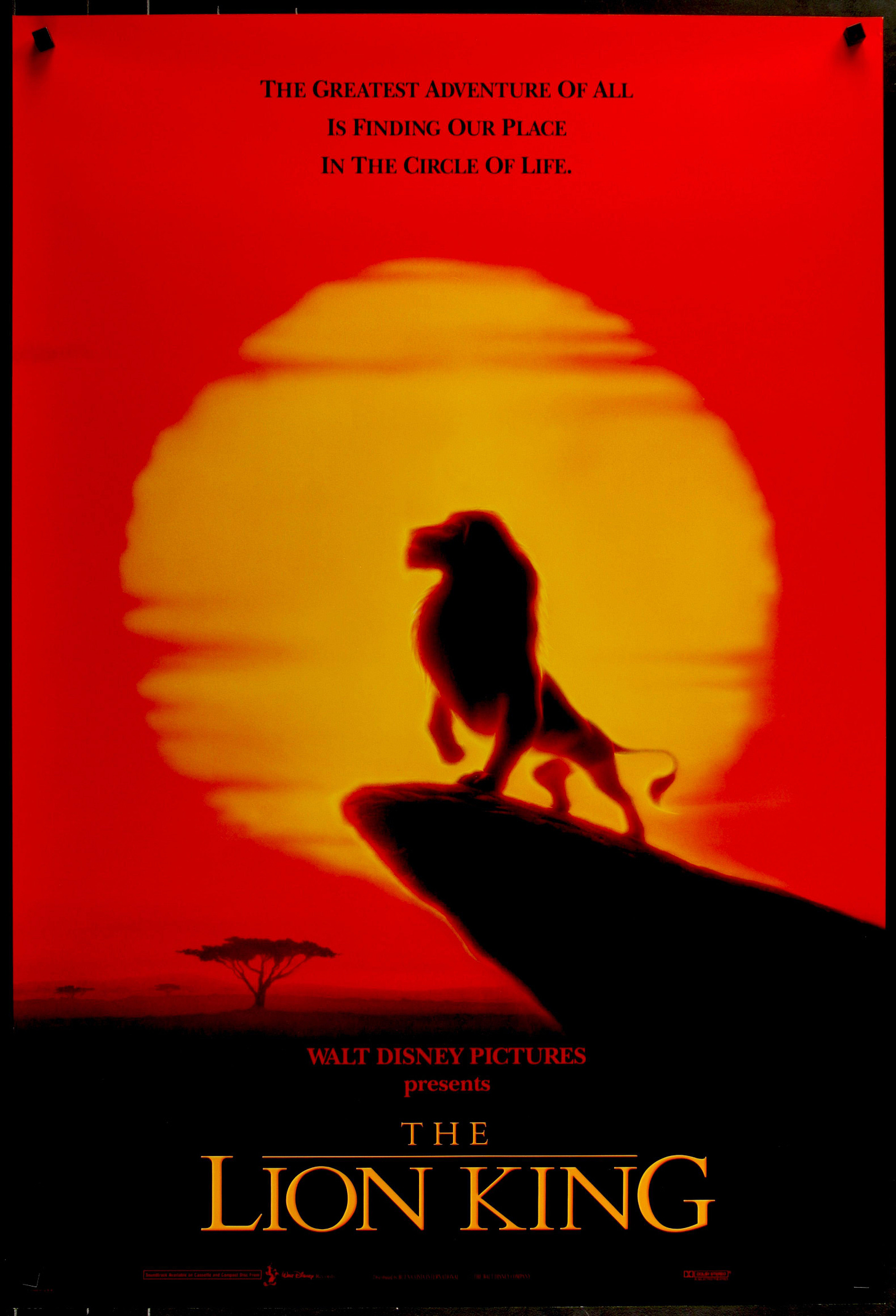

One of the greatest cultural shifts over the last few years has been the realization of how evil The Walt Disney Company is. As a Floridian, I’ve long hated the rat. However, most people considered it harmless at worst and magical at best. But there has finally been a shift that the average conservative looks at the entire corporation with complete disdain. However, it is worth remembering that the magical fuzzy feelings did not come from nowhere. There was some good in Disney once, there was lots of good in it once actually. I was reminded of this this past week when my school put on our annual musical, this year: The Lion King. I was reminded how incredibly good some of the lessons of this movie are. In particular, I found myself constantly drawn back to a Christian conception of kingship.

Simba, the young Lion Prince, sings “I Just Can’t Wait To Be King,” where we see a child’s understanding of what being king is. Ultimately Simba views kingship as simply being the person who cannot be told what to do and as such he is free in the more modern sense of the word - liberally free to just do whatever he wants. Zazu, a key advisor in teaching Simba his responsibilities, attempts to explain instead that the king has roles much more in line with the classical conception of freedom - the power to do what you ought. Zazu does not get through very much at all to Simba but he later gets a much more impactful lesson in this from his dad, Mufasa, the ideal king.

When Simba says to his dad that “I thought a king can do whatever he wants,” he is told that on the contrary “There is more to being king than getting your way all the time.” After this Mufasa breaks down his role in the incredibly famous Lion King song where he explains “The Circle of Life.” This is still Disney and not an actually Christian production so as a result the lesson is taught in hippy or pagan terms that the mystical circle of life moves us all. However, the lesson itself is deeply Christian. It effectively explains that each animal ultimately has its own needs and desires that are natural to it and that it is the job of the king to keep this in balance in a way that, while this terminology is not used exactly, maintains the common good. Mufasa is almost directly teaching the lesson that St. Thomas gave King Hugh II of Cyprus in De Regno, “If, therefore, a multitude of free men is ordered by the ruler towards the common good of the multitude, that rulership will be right and just, as is suitable to free men.”

As the plot progresses, Mufasa ultimately shows what being a king really means when he gives his life for Simba. Scar, Mufasa’s brother and second in line to the throne after Simba, arranges a plot in which the only way Simba can live is at the cost of Mufasa’s own life. Mufasa gladly pays the price. While this may or may not have been the movie’s actual intention, it clearly looks a whole lot like the example set by the one true King of Kings: Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends. We see the real cost of kingship and we see it is significantly more burdensome than doing whatever you want. This harkens to St. Thomas’ juxtaposition of bad roman emperors with the people when he states that “when many emperors of the Romans tyrannically persecuted the faith of Christ, a great number both of the nobility and the common people were converted to the faith and were praised for patiently bearing death for Christ.” In the real world a king’s job is not to do whatever he wants, it’s not even just to promote the common good, it is to actively take up his cross and patiently bear death for Christ. This is what we see in real Christian kings. This is why the icon for one of my favorite Christian kings there ever was, Blessed Emperor Karl, is not just Emperor Karl ruling but rather him being presented two crowns from two angels. One is the crown of St. Stephen that he wore at his coronation as King of Hungary, but the other crown is the crown of thorns to show the suffering he will bear for his people and the faith that he will have to unite to the sufferings the greatest King bore for him.

Following his death, we are presented with the perfectly imperfect example of a bad king: a tyrant. It is often understood that some sort of democracy like we have today is the opposite of kingship but St. Thomas wisely guides that kingship is the best version of the rule by a single man so its rightful opposite would be the worst perversion of the rule by a single man: “Kingship is the opposite of tyranny since both are carried on by one person. Now, as has been shown above, monarchy is the best government. If, therefore, ‘it is the contrary of the best that is worst.’ it follows that tyranny is the worst kind of government.” We see this to be true in Scar. Scar rules for his own good rather than the common good and what comes next is the natural consequence of that. Rather than each member of the multitude getting what is proper to it, the hyenas get a disproportionate amount causing them to become a ruling class and enforcement for Scar. It becomes the lionesses’ job to do all of the hunting for the pride. This is a particularly interesting way to show the perversion because in actual lions the lionesses are the primary hunter but this clearly shows what would be a perversion in human society. All in all we see exactly the tyranny that is explained by St. Thomas stating “If, on the other hand, a rulership aims, not at the common good of the multitude, but at the private good of the ruler, it will be an unjust and perverted rulership. The Lord, therefore, threatens such rulers, saing by the mouth of Ezekiel: ‘Woe to the shepherds that feed themselves (seeking, that is, their own interest): should not the flocks be fed by the shepherd?”

The Lion King is ultimately full of other valuable lessons about growing up, manhood, justice, and several other virtuous points. However, the clear and away overarching message is one of good kingship. While it is unlikely this was really the intended lesson, it is understandable why the kids who grew up in this era of Disney found it magical. In moments of confusion, fear, or retreat, Mufasa’s words echo what every true ruler — and every man striving for virtue — must hear:

Remember who you are.

LEO REX

Behold young Simba, lion cub and heir,

Who longs to rule and do just as he pleads.

He sees a crown as freedom without care,

There’s more to reign than chasing selfish deeds.

Yet Scar, who shows what such a dream becomes,

Lets Pride Rock starve while hyenas are fed.

He rests while lionesses hunt for crumbs,

And feeds himself while all the flock grows dead.

But Mufasa, the king both strong and just,

He saw the circle turn for all, not one.

Like Karl, he ruled with mercy, truth, and trust,

And bore the yoke so others would not fall.

So learn from kings who live for more by far:

To rule in love — remember who you are.